Posthuman science communication heroes: What science communicators are up with (or against)

Title: Steak and bleach as science communication heroes? The rise of post-corona, posthuman irony

Author(s) and Year: Pádraig Murphy

Journal: Journal of Science Communication (open access)

Soon after the COVID-19 pandemic hit, global and national health leaders like the WHO and CDC were struggling to properly disseminate accurate and accessible information amidst the floods of misinformation sweeping the media and threatening the safety and health of global societies.

Meanwhile, several companies used health and science communication-based marketing tools to engage with their social media followers around pandemic topics. This “posthuman” tactic for brands to claim human-like characteristics, such as strength (Mr. Clean), charm (the Geico gecko), and intelligence (Mac’s Justin Long), to engage with a target audience is commonly used in advertising and marketing to improve brand image and consumer relationships. In a 2015 article in The Guardian, Tracey Follows referred to posthumanism in brands as the brands’ attempt to claim an “augmented” human identity that is “tracking, hacking, monitoring, predicting, augmenting, creating, and recording us and our surrounding environment to improve, augment, or enhance our health and wellbeing.”

During the pandemic, private companies used their “posthuman” identities to not only increase engagement with matters relevant to their brands but to also communicate and defend scientific facts through irony and humor, regardless of the relevance that those brands may have to matters of science and health. Murphy questions in this Journal of Science Communication article whether affect-based marketing that incorporates posthumanism is the way we should go about promoting science literacy and engagement (which are supposedly areas that require more logic). Murphy concludes that although this posthuman communication may help to increase the visibility of science communication topics in the media, this type of communication can turn toxic when the brands’ posthuman voices drown out the voices of health and science experts.

Murphy reached this conclusion by using science communication and science and technology studies (STS) theories and approaches to analyze online and social media outputs of 100 popular brands. Such outputs included company statements, tweets, ad campaigns referencing COVID-19, and corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies and responses to the pandemic.

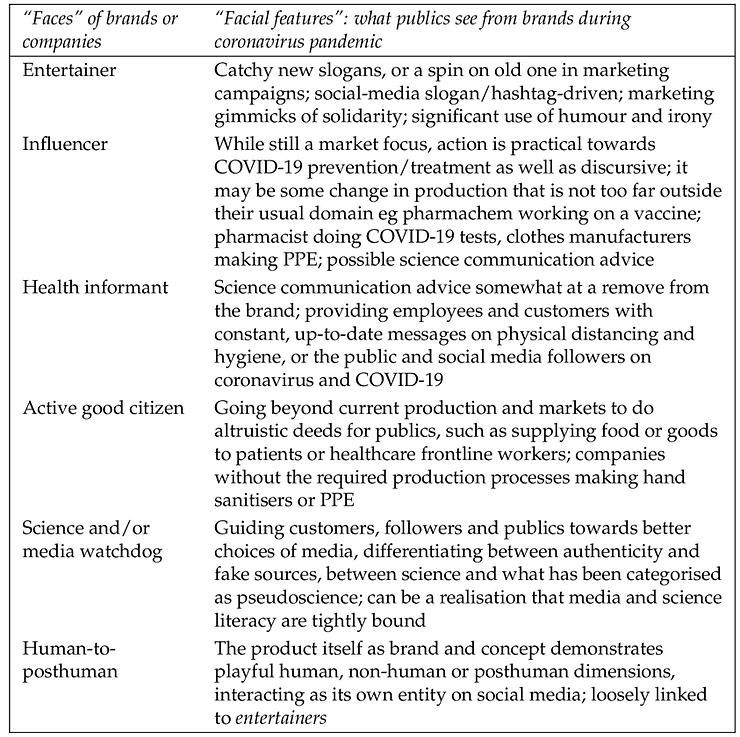

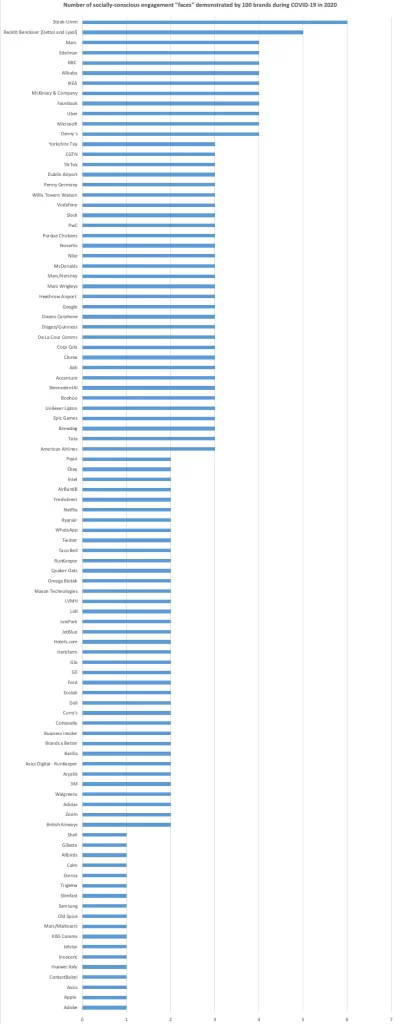

The analysis produced a classification (typology) of brand strategies based on the way scientific information about COVID-19 was communicated. In Table 1 below, Murphy lists the various brand “faces,” or the types of brand persona communicating about COVID-19. He found that brands claimed one or more of the following communicator persona: the entertainer, the influencer, the health informant, the active good citizen, the science and/or media watchdog, and the human-to-posthuman. Of the brands analyzed, the frozen beef brand Steak-umm was the only company that had exhibited all six of those faces on various occasions. Disinfectant brands, such as Dettol, Lysol, and Clorox (bleach), exhibited four (Figure 1).

Features of the “faces” claimed by different brands reveal a full spectrum of communication strategies that companies used to engage the public with scientific information. Such multifaceted strategies were demonstrated in the paper through the exemplar case of Steak-umm.

During the pandemic, Steak-umm became a champion of social justice and a “posthuman expert in science and media affairs” by demonstrating reflexivity in critiquing ineffective media coverage of science and social justice issues. The brand received attention and support for its simultaneously lighthearted and serious posts about the need for a critical thinking society. This position went as far as challenging the epistemological position of Neil deGrasse Tyson in April 2021. While Tyson confounded the meaning of science and truth, the frozen meat started a beef with him on the basis of how such a science communication strategy turns people away from science. This brand hero is thus not only a critic of corporate control of information and misinformation, but also of science communication strategies.

Murphy cautiously rejoices in the effects that moral capital can potentially have on health and environmental communication. Although the paper does not really claim to draw conclusions regarding the extent to which such engagement has benefitted (or harmed) science communication, the brands, or the public, it does reflect on some potential implications for practicing science communicators.

Potentially, blending social causes with for-profit brands can create “toxic hybridity” that can discount the cause in the public mind, especially given obvious questions of authority and impartiality, the perceived low credibility of social media content, and contradictory calls that warn people from using social media for accurate health and science advice. The ultimate danger that Murphy concludes with, however, is when companies communicate about sensitive scientific topics in a voice that is louder than the experts in fields of science and technology.

With misinformation threatening the safety and health of global societies and the prospects of a new scary era defined by global crises that require disparate actions, Murphy points out how risky it is to allow corporations to take over science communication spaces. This brings us to the challenging, seemingly impossible, role that modern science communicators, whether in public or private institutional roles, need to assume in order to compete with flashy posthuman brands: a role that is simultaneously informative, effective, entertaining, and activist. As Murphy puts it:

The increased hybridised, intermediary position of the science, health or environmental communicator means they now have opportunities to play, critique and shape-shift online, and challenge both capitalist idealism and deliberate disinformation — and in the process be posthuman if they need to be, with added humanity.

Written by: Niveen AbiGhannam

Edited by Jacqueline Goldstein

Cover image credit: Steak-Umm Twitter